In the dynamic world of business, organizations must continuously evolve and adapt to remain competitive. The strategic management of capabilities is crucial for achieving this, with dynamic capabilities and original capabilities representing two fundamental paradigms. In this blog post, we delve into the concepts of dynamic capabilities from an architecture perspective, clarifying their similarities and differences. Additionally, we explore insights supported by relevant references.

What are dynamic capabilities

Dynamic capabilities refer to an organization’s ability to adapt, innovate, and change in response to rapidly changing external environments. These capabilities are critical for an organization’s long-term success and competitiveness. Dynamic capabilities go beyond an organization’s static or routine abilities and involve the capacity to reconfigure and recombine its resources and competencies to address new challenges and opportunities.

There are three types of dynamic capabilites:

- Sensing. Finding and assessing opportunities outside the organization. This involves an organization’s ability to perceive and recognize changes in its external environment, such as shifts in customer preferences, emerging market trends, technological advancements, and competitive threats. Effective sensing requires a keen understanding of the business ecosystem and the ability to gather and analyze relevant information.

- Seizing (or Mobilizing). Mobilising the resources to acquire value from those chances. This means identifying changes and opportunities to enable dynamic capabilities so that an organization can effectively seize or exploit them. This involves making strategic decisions and taking actions to capitalize on the identified opportunities, often by reallocating resources, developing new products or services, or entering new markets.

- Reconfiguring (or Transforming). Changing the organization to support opportunities. Dynamic capabilities also involve the ability to reconfigure the organization’s internal resources, processes, and capabilities to align with the new strategic direction. This may require changes in the organization’s structure, culture, technology, and human capital to support the seizing of new opportunities and the addressing of emerging challenges.

Adapting to change

Dynamic capabilities, a term coined by David Teece in the 1990s, are an integral part of strategic management. These capabilities encompass an organization’s ability to reconfigure its resources and processes to respond effectively to changing market conditions, emerging opportunities, and evolving customer needs [1]. Dynamic capabilities are characterized by agility, flexibility, and a penchant for learning and innovation.

One of the key advantages of dynamic capabilities is their adaptability. Organizations equipped with strong dynamic capabilities can swiftly adjust their strategies, reallocate resources, and even overhaul their business models in response to dynamic market forces. This adaptability serves as a proactive approach to navigating uncertainty and competition [2]. Business architecture plays a considerable role here.

Furthermore, dynamic capabilities emphasize continuous learning and innovation. Organizations that foster these capabilities are more likely to experiment with novel ideas, technologies, and processes. This commitment to innovation enhances their long-term competitiveness and ability to sustain growth [3].

However, these capabilities also present challenges. Developing and maintaining them demands substantial investments in terms of time, resources, and management commitment. Managing change and uncertainty can lead to employee resistance and organizational stress. Nevertheless, when executed effectively, these capabilities can serve as a formidable source of sustainable competitive advantage, as they are challenging for competitors to replicate.

Stability and efficiency

Original capabilities, also known as core capabilities or static capabilities, represent an organization’s foundational skills, processes, and resources. These capabilities are deeply embedded in the organization’s culture and structure, serving as the bedrock upon which its operations are built. Original capabilities are relatively stable over time and constitute the organization’s baseline strengths.

Stability is a hallmark of original capabilities. They provide organizations with a dependable foundation for their operations, rooted in the accumulated knowledge and expertise developed over time. This stability ensures consistency and reliability in performance, a critical factor in industries where predictability is paramount.

Efficiency is another key advantage of original capabilities. These capabilities are typically well-established and optimized for efficient execution. This optimization leads to cost savings and operational excellence, allowing organizations to maintain a competitive edge in terms of resource utilization.

However, the overreliance on original capabilities can pose challenges. In rapidly changing environments, organizations that cling to these static capabilities without adapting or evolving risk becoming obsolete. Additionally, original capabilities may slow an organization down, making it challenging for organizations to change when necessary.

Comparing capabilities

Similarities

- Both dynamic and original capabilities contribute significantly to an organization’s overall performance and competitiveness.

- They are shaped by an organization’s culture, leadership, and strategic decisions.

- Effective management and alignment with the overall enterprise architecture are critical for maximizing the benefits of both types of capabilities.

Differences

- Dynamic capabilities focus on adaptability, change, and innovation, while original capabilities emphasize stability, consistency, and efficiency.

- Dynamic capabilities are more responsive to external market changes, whereas original capabilities are more internally focused and less adaptable to external disruptions.

- Dynamic capabilities are often associated with future-oriented strategies, whereas original capabilities are grounded in historical strengths.

A pragmatic example

Now, Apple is often cited as an organization that understands dynamic capabilities and acts on them. Apple seems to have a knack for understanding the consumer market and knowing exactly how and when to adapt the internal organizational processes to meet external demand.

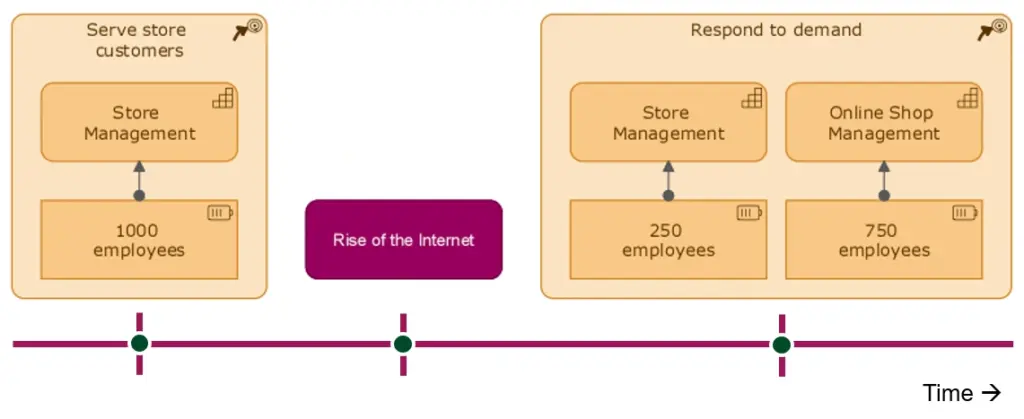

To put this into a simplified example, we could argue that Apple once leveraged a capability we will call Store Management. The resources allocated to this capability consisted of 1000 employees manning stores around the world (remember, this is a fictional example).

Over time, the rise of the Internet and the opportunities it created for consumers quickly became overwhelming. Apple had to respond to these growing opportunities.

Apple sensed that customers would want to be able to order their latest cell phone over the Internet. They seized the opportunity to offer the phones online, and in order to do so, they had to reconfigure the resources they were spending on the Store Management capability.

Using dynamic capabilities, they were able to recognize the need to create a new capability, which we will call Online Store Management. Apple also needed to adjust the resources allocated to the former capability, Store Management, by spreading them across the two existing capabilities (Online Store Management and Store Management).

Using the TOGAF® Standard

The TOGAF Standard can be used for an applicable deployment of capabilities. The current version of the framework allows for Agile solutions and therefore fits seamlessly into the context of dynamic capabilities.

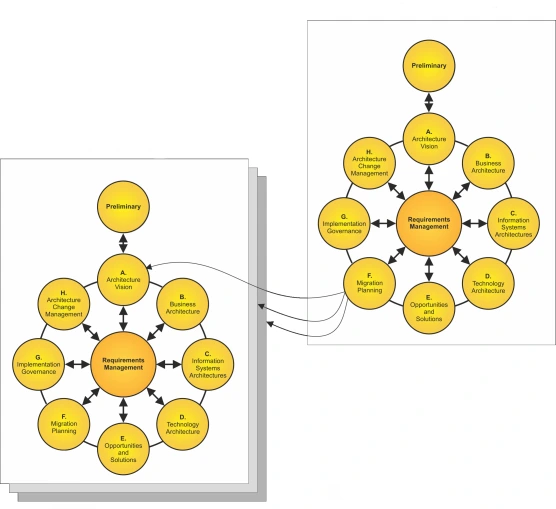

The TOGAF Standard uses the Architecture Development Method (ADM) to interpret the architecture process. The ADM is fully iterative and allows for iteration upon iteration to arrive at an appropriate set of capabilities. Where dynamic capabilities require the organization to change, the ADM provides ways to respond appropriately.

As the iteration progresses, Phase B (Business Architecture) involves naming and creating the capabilities that respond to the identified (sensed) market demand. The ADM cycle then continues through to Phase E (Opportunities and Solutions). Here it is determined whether there are any constraints on the design of the capabilities, what other requirements need to be met, and whether any other gaps need to be addressed.

In Phase F (Migration Planning), the newly created capabilities are tested to see if they provide a sufficient response to the required changes. For example, the resources required for the capabilities are allocated. If the tests indicate that the capabilities are not adequate, a new iteration of the ADM can be started.

In this way, the Architecture Development Method provides ample opportunity to arrive at an appropriate and workable solution. A solution that allows the organization to adapt, change and innovate.

Conclusion

In conclusion, dynamic capabilities and original capabilities are two indispensable paradigms in architecture. While dynamic capabilities enable organizations to adapt, innovate, and excel in changing environments, original capabilities provide stability, consistency, and efficiency in day-to-day operations. Achieving success in the modern business landscape necessitates striking the right balance between these two types of capabilities. I wrote about the need for using capabilities in an earlier blog post, although that blog post accentuated the use of capabilities in relation to collaboration.

Organizations should leverage original capabilities as a sturdy foundation while nurturing dynamic ones to remain competitive and responsive to market dynamics. Ultimately, those who can effectively manage both forms of capabilities will be better equipped to navigate the ever-evolving business landscape and secure their position in an increasingly competitive world.

So, do you agree with me? Perhaps you have a different opinion? Please share it with me in the comments section below.

[1] Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319-1350.

[2] Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21(10-11), 1105-1121.

[3] Helfat, C. E., & Peteraf, M. A. (2009). Understanding dynamic capabilities: Progress along a developmental path. Strategic Organization, 7(1), 91-102.

Leave a Reply